Vasanth

Feb 9, 2026

The regulatory challenge of managing per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances has reached a scale that manual compliance processes cannot absorb. With the EPA's TSCA Section 8(a)(7) reporting rule requiring manufacturers and importers to reconstruct over a decade of PFAS activity, enterprises face a reporting burden that demands structural change in how compliance data is gathered, validated, and submitted. TSCA Section 8(a)(7) PFAS compliance automation has become a strategic necessity for any organization operating across global supply chains. As both federal and state-level regulatory pressure intensifies simultaneously, the organizations that invest in AI-native compliance automation will establish the operational foundation required for sustained market access.

For a comprehensive analysis of why no manufacturer can consider themselves exempt from the global PFAS regulatory wave, see PFAS Compliance in 2026: Why "Out of Scope" No Longer Exists for Global Manufacturers.

Table of Contents

Executive Regulatory Overview

TSCA Section 8(a)(7): Framework Background and Legal Scope

Key Reporting Requirements and Thresholds

Affected Industries and Product Categories

Reporting, Documentation, and Data Challenges

Compliance Risks, Penalties, and Enforcement Exposure

Supply Chain and Operational Impact

Timeline and Future Enforcement Outlook

Strategic Compliance Preparation Checklist

The Role of AI in Managing TSCA Section 8(a)(7) Compliance

Executive Conclusion: From Regulatory Burden to Competitive Advantage

Executive Regulatory Overview

PFAS represent one of the most operationally complex categories of regulated substances in modern manufacturing. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) revised its definition of PFAS in 2021 to encompass any fluorinated substance containing at least one fully fluorinated methyl or methylene carbon atom. Under this broadened structural definition, databases such as PubChem now identify over 7 million compounds that technically qualify as PFAS, while the EPA's CompTox Chemicals Dashboard lists over 14,000 structures in its most recent PFAS classification. Commonly cited estimates place the number of commercially relevant PFAS compounds in the range of 10,000 to 15,000.

For enterprises, this scale creates an extraordinary identification challenge. Unlike regulations that target a fixed list of named substances, TSCA Section 8(a)(7) relies on a structural definition. Any substance meeting one of three specified molecular patterns falls within scope, regardless of whether it appears on EPA reference lists. This means organizations cannot depend solely on published inventories and must build the analytical capability to evaluate substances at the molecular level across their entire product portfolio. Traditional manual compliance approaches collapse under this complexity. Automated regulatory monitoring becomes essential when the substance universe itself is defined by structure rather than enumeration.

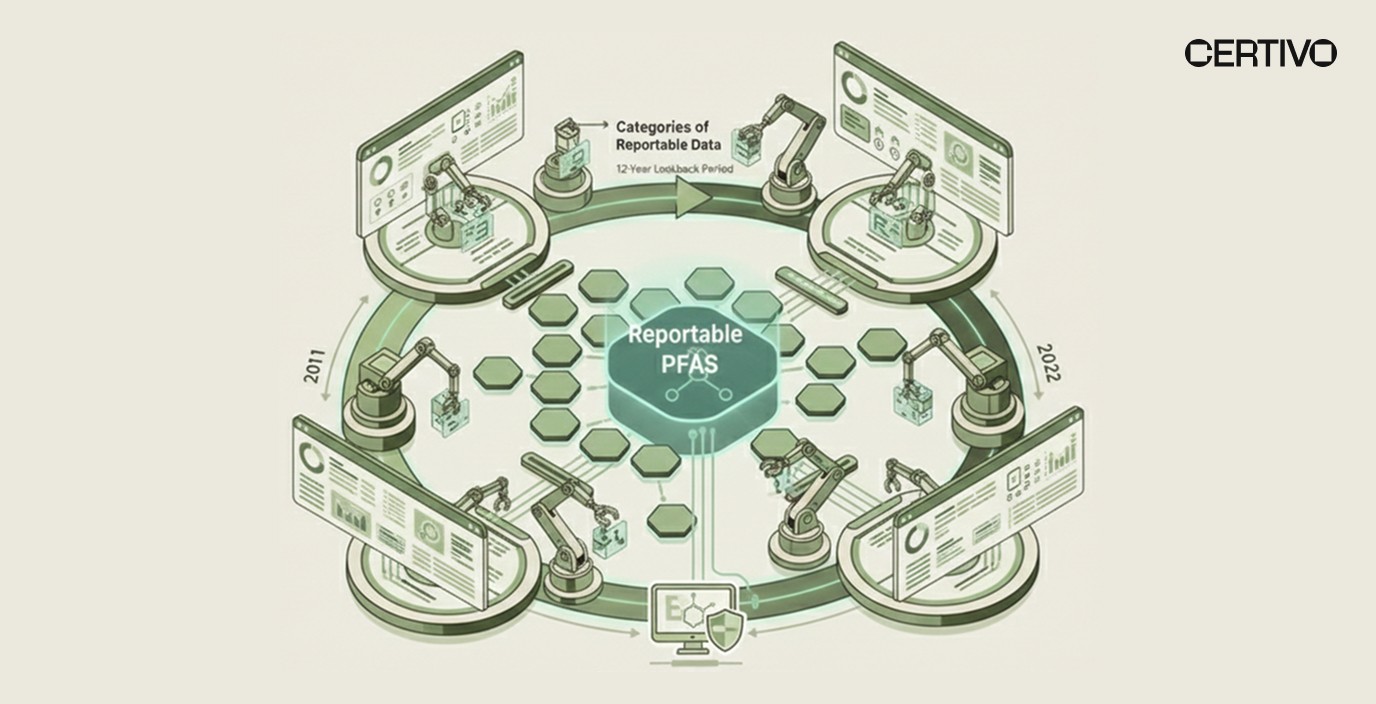

The rule's one-time retrospective reporting requirement, covering manufacturing and import activity from January 1, 2011, through December 31, 2022, adds another dimension of difficulty. Companies must reconstruct a 12-year history of PFAS-related activity across product lines, suppliers, and facility operations — a task that demands both deep supply chain visibility and robust supplier data management infrastructure.

TSCA Section 8(a)(7): Framework Background and Legal Scope

Congress mandated the creation of this reporting rule through the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2020, which amended Section 8(a)(7) of the Toxic Substances Control Act. This statutory mandate left the EPA with limited discretion over whether to issue the rule, though the Agency retained authority over its scope and implementation.

The EPA finalized the rule on October 11, 2023, establishing what will become the largest-ever database of PFAS manufactured and used in the United States. Under the final rule, any person who has manufactured (including imported) PFAS or PFAS-containing articles for commercial purposes in any year since January 1, 2011, must electronically report detailed information to EPA. The reporting standard requires disclosure of all information "known to or reasonably ascertainable by" the reporting entity, which EPA interprets as requiring reasonable due diligence, including inquiries to upstream suppliers.

EPA's Definition of Reportable PFAS

For the purposes of this rule, EPA has defined PFAS using a structural approach. A chemical substance is considered a PFAS if it contains at least one of three molecular sub-structures involving saturated carbon-fluorine bonds. EPA has identified at least 1,462 PFAS currently on the TSCA Chemical Substance Inventory that may be covered by this rule, with 770 on the active inventory indicating current U.S. commercial use. This definition is narrower than the OECD's broader classification but still encompasses a vast universe of chemicals that many manufacturers have never previously tracked or reported.

Understanding this structural definition is critical for compliance managers and regulatory teams. For a deeper examination of this specific reporting obligation, review Certivo's analysis of PFAS TSCA Section 8(a)(7) reporting requirements and what manufacturers must do now.

Key Reporting Requirements and Thresholds

The scope of reportable information under TSCA Section 8(a)(7) is significantly broader than most TSCA data collection rules. For each PFAS manufactured or imported at each site, companies must report the following categories of data on a per-chemical, per-site, per-year basis across the entire 2011–2022 lookback period:

Reportable Data Categories

Chemical identity and structure: Common and trade names, molecular structure, and Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers for each PFAS substance or mixture.

Production volumes and usage categories: Total and category-specific amounts of PFAS manufactured or processed, with estimates for proposed amounts. Current or proposed usage categories for each substance.

Byproduct information: Descriptions of byproducts from the manufacture, processing, use, or disposal of each PFAS substance.

Environmental and health effects: All existing information concerning environmental and health effects, submitted using the OECD harmonized template (OHT) format.

Worker exposure data: Number of individuals exposed or estimated to be exposed to PFAS substances at work, along with duration of exposure.

Disposal methods: Current disposal methods and any changes in methods for each PFAS substance.

Proposed Exemptions Under the November 2025 NPRM

In November 2025, EPA published a proposed rule to amend the scope of the reporting regulation. The proposed exemptions include PFAS at concentrations below 0.1 percent in mixtures or articles (de minimis), PFAS imported as part of an article, byproducts not used commercially, impurities, non-isolated intermediates, and small quantities manufactured solely for research and development. EPA has also requested comments on whether the de minimis threshold should be set at 1.0 percent instead.

These proposed changes, if finalized, would narrow the reporting universe. However, the core obligation — that manufacturers and importers of PFAS for commercial purposes must report — remains intact. The final rule is anticipated in or around June 2026, according to the Spring 2025 Unified Regulatory Agenda.

Organizations already invested in specialized substance reporting solutions and audit-ready documentation will be better positioned to adapt to either outcome. Those operating with spreadsheet-based or fragmented compliance systems risk being unprepared regardless of which exemptions survive the final rule.

Affected Industries and Product Categories

The reach of TSCA Section 8(a)(7) extends well beyond the chemical manufacturing sector. PFAS are embedded in products across virtually every major industry due to their resistance to water, heat, oil, and stains. EPA specifically identifies the following sectors as potentially affected: chemical manufacturing and distribution, construction, retail and wholesale trade, electronics manufacturing, automotive production, aerospace and defense, semiconductor fabrication, medical device manufacturing, textile and apparel production, food packaging, energy storage and battery systems, and waste management services.

The inclusion of article importers in the original rule's scope was particularly consequential, pulling in a vas range of companies that import finished goods containing PFAS. While the November 2025 proposed rule would exempt imported articles, this exemption is not yet finalized. Organizations importing articles should continue to prepare their reporting infrastructure as if the exemption may not survive.

Companies in sectors such as industrial electronics and industrial automation face particular complexity because PFAS may be present in components, coatings, lubricants, and processing aids used at multiple tiers of the supply chain. Without BOM-level compliance intelligence, identifying all reportable PFAS across thousands of components is practically impossible through manual compliance efforts alone.

Reporting, Documentation, and Data Challenges

The data collection requirements under TSCA Section 8(a)(7) represent one of the most demanding reporting burdens in the history of U.S. chemical regulation. Several structural factors make this rule uniquely difficult to operationalize.

The Lookback Problem

The 12-year retrospective reporting window (2011–2022) requires companies to reconstruct historical manufacturing, import, and use data that may predate current record-keeping systems, personnel, and even corporate structures. For organizations that have undergone mergers, acquisitions, or ERP migrations during this period, locating and validating historical data across legacy systems is a formidable challenge. Regulatory tracking across this timeframe demands data archaeology at enterprise scale.

Structural Definition Complexity

Because the rule uses a structural definition rather than a named substance list, organizations must evaluate whether each chemical in their portfolio meets one of three molecular patterns. This requires analytical capabilities that many compliance teams lack. A centralized compliance infrastructure is essential for mapping structural definitions against bills of materials and supplier declarations.

The Supplier Data Gap

The "known or reasonably ascertainable" reporting standard effectively requires companies to conduct due diligence extending into their supply chains. For enterprises managing hundreds or thousands of suppliers globally, collecting chemical-specific data using standardized supplier questionnaire frameworks represents a massive coordination challenge. Many suppliers, particularly those in Asia-Pacific regions, may not have detailed PFAS composition data readily available. Multi-tier supply chain transparency becomes a practical requirement, not an aspirational goal.

Electronic Submission Through CDX

All data must be submitted electronically through EPA's Central Data Exchange (CDX) portal. The CDX reporting application has been under development and has experienced significant delays, contributing to multiple extensions of the submission period. Companies must register with CDX and add the CSPP program to their accounts in advance of the portal opening.

Compliance Risks, Penalties, and Enforcement Exposure

Noncompliance with TSCA Section 8(a)(7) constitutes a violation of TSCA Section 15(3). The enforcement consequences are substantial and carry both financial and operational implications.

Penalty Structure

TSCA violations can result in civil penalties up to the statutory maximum of $46,989 per violation, subject to annual inflationary adjustments. Critically, each unreported PFAS at each site constitutes a separate violation. For a manufacturer with multiple facilities and dozens of reportable substances, potential penalty exposure can escalate rapidly into millions of dollars. In 2025, EPA assessed its single largest TSCA penalty of $700,000 for Chemical Data Reporting (CDR) rule violations involving 334 unreported imported chemicals, demonstrating that the Agency actively enforces chemical reporting obligations.

Citizen Suit Exposure

TSCA Section 20 grants private citizens the authority to bring civil actions against companies for TSCA violations. Environmental NGOs have increasingly utilized this provision, reviewing EPA's public CDR database to identify potential non-reporters and filing lawsuits to compel corrective reporting, restrain ongoing violations, and recover attorneys' fees. This creates audit risk that extends well beyond direct EPA enforcement.

Reputational and Market Access Implications

Beyond direct penalties, noncompliance can affect ESG ratings, customer due diligence assessments, and access to markets with overlapping PFAS restrictions. Organizations already navigating REACH SVHC obligations and EU-level PFAS restrictions will find that a TSCA reporting failure signals broader compliance fragility to customers and investors.

Supply Chain and Operational Impact

TSCA Section 8(a)(7) does not exist in isolation. Its reporting demands intersect with a growing network of federal and state PFAS regulations that collectively reshape how manufacturers manage substances across their operations.

Converging Federal and State Obligations

While TSCA Section 8(a)(7) establishes the federal reporting baseline, individual states are implementing their own PFAS restrictions with independent timelines and thresholds. Massachusetts, Connecticut, Minnesota, Washington State, and New Jersey have all enacted or proposed PFAS-specific laws covering reporting, labeling, or outright product bans.

International Regulatory Convergence

The regulatory pressure extends internationally. The EU is advancing its own comprehensive PFAS restriction proposal, the UK has implemented firefighting foam bans, and France has enacted national PFAS restrictions. For global manufacturers, managing this convergence requires centralized regulatory tracking across jurisdictions rather than siloed compliance programs.

Operational Implications for Procurement and Product Development

The data gathered during TSCA Section 8(a)(7) compliance preparation has direct value beyond the reporting obligation itself. Organizations that invest in building supplier risk scoring ecosystems and comprehensive substance inventories now will be better prepared for future PFAS restrictions, reformulation requirements, and customer disclosure demands. This data also supports digital product passport enablement requirements emerging in the EU under the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation.

Timeline and Future Enforcement Outlook

The TSCA Section 8(a)(7) timeline has evolved significantly since the rule was first finalized. Understanding the current status and anticipated changes is critical for compliance planning.

Current Timeline (Interim Final Rule — May 2025)

The data submission period opens April 13, 2026, and closes October 13, 2026, for most manufacturers and importers. Small businesses reporting data solely on importing PFAS-contained articles have until April 13, 2027.

Anticipated Timeline (November 2025 Proposed Rule)

Under the proposed amendments, the reporting window would begin 60 days after the effective date of the final revised rule and remain open for three months (reduced from six). With a final rule anticipated in or around June 2026, the reporting window would likely open approximately September 2026 and close approximately December 2026. However, this timeline may shift depending on the rulemaking process and potential legal challenges.

Regulatory Horizon Beyond TSCA

Regardless of how the federal rule evolves, the regulatory trajectory for PFAS is accelerating. State-level obligations continue to expand, the EU packaging PFAS ban takes effect in 2026, and global PFAS regulations increasingly require substance-level data that organizations will need regardless. Regulatory horizon scanning intelligence — the ability to anticipate and prepare for upcoming obligations — is becoming a core competency for enterprise compliance teams.

Strategic Compliance Preparation Checklist

Enterprise compliance leaders should treat the following actions as immediate priorities, irrespective of the proposed exemptions currently under review.

Conduct a PFAS substance inventory. Map all chemicals, mixtures, and articles across your product portfolio against EPA's structural definition. Prioritize products with known fluorinated chemistry, coatings, and surface treatments.

Establish supplier data collection protocols. Deploy standardized questionnaire frameworks to request PFAS composition data from all tiers of your supply chain. Document all outreach efforts to demonstrate reasonable due diligence under the "known or reasonably ascertainable" standard.

Reconstruct historical records (2011–2022). Identify and consolidate production, import, and use data from legacy ERP systems, archived procurement records, and former business units. Address data gaps with documented rationale.

Register with EPA's CDX portal. Ensure your organization has active CDX accounts with the CSPP program added. Assign internal roles for data entry, review, and submission.

Evaluate proposed exemptions against your operations. Determine which, if any, of the proposed exemptions (de minimis, articles, byproducts, R&D, impurities) would reduce your reporting scope if finalized. Do not assume exemptions will survive the final rule process.

Integrate TSCA reporting with broader PFAS compliance infrastructure. The data you collect for Section 8(a)(7) has direct value for state-level reporting obligations, EU PFAS restrictions, and customer due diligence requests. Build your data architecture for reuse across multiple frameworks.

Assign executive ownership. PFAS compliance carries board-level financial and reputational risk. Ensure accountability sits at the VP or C-suite level, not solely within EHS teams.

The Role of AI in Managing TSCA Section 8(a)(7) Compliance

The scale, complexity, and retrospective nature of TSCA Section 8(a)(7) make it an ideal use case for AI compliance software. The volume of substances, sites, years, and data categories involved overwhelms traditional compliance workflows. Intelligent compliance platforms fundamentally change how organizations approach this challenge.

Substance Identification and Structural Screening

AI-powered systems can screen chemical inventories against EPA's structural PFAS definition at speeds and accuracy levels impossible through manual review. This is particularly valuable when evaluating complex mixtures, polymers, and proprietary formulations where PFAS may be present as processing aids, coatings, or unintentional byproducts. AI compliance software enables organizations to move from reactive identification to systematic, continuous screening.

Automated Supplier Data Collection

Platforms like Certivo use CORA to operationalize supplier data collection at scale. Rather than relying on manual email campaigns and spreadsheet tracking, CORA enables structured data collection from suppliers through centralized supplier self-service portals, reducing the compliance team's administrative burden while improving response rates and data quality. This approach to AI in supply chain compliance management transforms what was previously a months-long manual effort into a managed, trackable workflow.

Continuous Audit-Ready Documentation

Compliance with TSCA Section 8(a)(7) is not a one-time reporting event — it establishes a permanent compliance record that EPA, NGOs, and customers may reference. Maintaining continuous audit-ready documentation requires a system of record that preserves evidence of due diligence, supplier outreach, data validation decisions, and submission history. Certivo functions as this system of record, ensuring that compliance evidence is structured, timestamped, and retrievable long after the reporting window closes.

Regulatory Change Monitoring and Multi-Framework Management

PFAS compliance does not end with TSCA. As state and international regulations continue to evolve, organizations need automated regulatory monitoring that tracks changes across jurisdictions and maps them to affected products and substances. The ability to manage compliance risk proactively — rather than scrambling when deadlines approach — is what distinguishes operationally mature compliance programs from reactive ones.

Integrated PLM ERP Compliance

For enterprises with complex product lifecycles, integrating compliance intelligence into existing PLM and ERP systems ensures that PFAS data flows naturally through product development, procurement, and manufacturing processes. This integration eliminates the data silos that make retrospective reporting so painful and positions organizations for continuous market readiness rather than periodic compliance exercises.

Executive Conclusion: From Regulatory Burden to Competitive Advantage

TSCA Section 8(a)(7) PFAS compliance automation is not simply about meeting a federal reporting deadline. It is about building the data infrastructure and operational capability that enterprise manufacturers need to navigate an accelerating global PFAS regulatory environment.

The organizations that treat this rule as an isolated reporting obligation will face the same data gaps, supplier opacity, and audit risk every time a new PFAS regulation takes effect, whether at the federal, state, or international level. Those that invest in AI compliance software, structured substance data, and centralized regulatory tracking will convert a regulatory burden into lasting operational value.

The PFAS regulatory trajectory is clear: more jurisdictions, more substance coverage, lower thresholds, and stricter enforcement. The question for enterprise leaders is not whether to automate PFAS compliance, but how quickly they can build the systems required to sustain it. For a complete analysis of what this means across all major PFAS jurisdictions, review PFAS Compliance in 2026: Why "Out of Scope" No Longer Exists for Global Manufacturers.

Explore how AI-driven compliance platforms like Certivo support long-term regulatory readiness. Connect with Certivo.

Vasanth

Vasanth is a skilled Compliance Engineer with over five years of experience specializing in global environmental regulations, including REACH, RoHS, Proposition 65, POPs, TSCA, PFAS, CMRT, EMRT, FMD, and IMDS. With a strong academic foundation in Chemical Engineering from Anna University, he brings a deep technical understanding to compliance processes across complex product lines.

Vasanth excels in analyzing Bills of Materials (BOMs), evaluating supplier declarations, and ensuring regulatory conformity through meticulous review and risk assessment. He is highly proficient in supplier engagement, adept at interpreting material disclosures, and experienced in preparing customer-ready compliance documentation tailored to diverse global standards.

Known for his attention to detail, up-to-date regulatory knowledge, and proactive communication style, Vasanth plays a critical role in maintaining product compliance and advancing sustainability goals within fast-paced, globally integrated manufacturing environments.